by Mike Moore

via CortesIsland.com

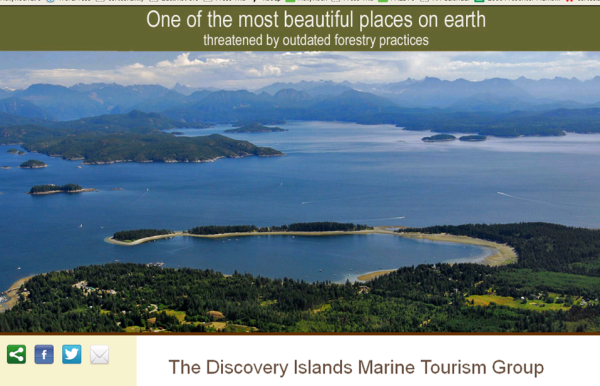

The Discovery Islands Marine Tourism Group published a full page ad in today’s Victoria Times Colonist to bring to light how the BC Liberals have neglected the environment to the detriment of tourism and in favour of short term profits by the logging industry.

There’s a new confrontation brewing in British Columbia forests and it’s coming from an unlikely source. The latest battle to protect Vancouver Island’s forests isn’t being waged by an environmental organization…it’s being waged by business: In particular, the tourism industry. A coalition of tourism businesses in the Discovery Islands, near Campbell River are charging the government with indifference to the needs of a major economic player in the region.

The Discovery Islands Marine Tourism Group is a coalition of businesses including the local Chamber of Commerce, which claims provincial forest policies designed by the BC Liberal government are encouraging the forest industry to clear cut forests along marine corridors which are critical to the survival of a large wilderness based tourism industry.

The group went public with its concerns by publishing a full page ad in the Victoria Times Colonist criticizing the government for its inaction. Spokesperson Ralph Keller says the group wanted to send a strong message to government that forest management polices aren’t working for Discovery Islands business, employees and their families. “We’ve spent a lot of time and money trying to convince the government there’s a serious problem here but they’re not listening.”

The Discovery Islands are home to over 120 tourism – dependent businesses: lodges, resorts, motels, campgrounds, marinas, tour companies, and related operations which employ over 1200 people and generate 45 million dollars in revenue every year. “The Discovery Islands have become a world class destination worthy of increased protection.” Keller said. “We’ve become the second most important marine wilderness destination in BC, behind Tofino/Pacific Rim, yet the government is managing the forests here like its 1956. They’re treating us like bystanders instead of major revenue producers and employers.” Keller went on to say that in the last 15 years, Vancouver Island has lost most of its pulp mills and saw mills and with them thousands of jobs—now out-sourced to Asia. “The once great forest industry is now just a logging industry acting with impunity, completely insensitive to our needs. They degrade our operating environment then send the timber not only out of the region, but out of the country. Is this supposed to be the BC Liberal commitment to jobs and families?”

“We’re not against logging, but when the government revised the Forest Range & Practices Act in 2003, they gave all the power to the logging industry and left every one else out of the planning process.” He went on to say that tourism operators are kept completely in the dark about cutting plans. “We find out about forest development plans when we start to see trees being felled. We’re being misled about forest industry intentions and have no meaningful way to influence cut blocks. When we complain to government, they tell us to go talk to the licensees…Who’s writing the rules here? Whose forests are these? It’s pretty clear this government is about corporate resource extraction and everybody else is just in the way”.

For more information go to: www.DiscoveryIslandsTourism.org

Or contact one of these business operators:

Ralph Keller, 250-285-2823

Ross Campbell: 250-202-3229

Michael Moore: 250-935-6756

Breanne Quesnel or John Waibel: 250-285-2121

Jack Springer: 250-287-2667

Philip Stone 250-285-2234

Our thanks to Daniel Pierce of Ramshackle Pictures for producing the video “Timber and Tourism in the Discovery Islands”! https://vimeo.com/61583243

Learn more at discoveryislandtourism.org

Forests for the Trees: Losing the Wild

by Ray Grigg

via Pacific Free Press